Schwere und Leichte

Artikelreferenz exportieren

- Klartext

- BibTeX

- RIS Format

- Downloadkosten : € 6.00

Zusammenfassung:

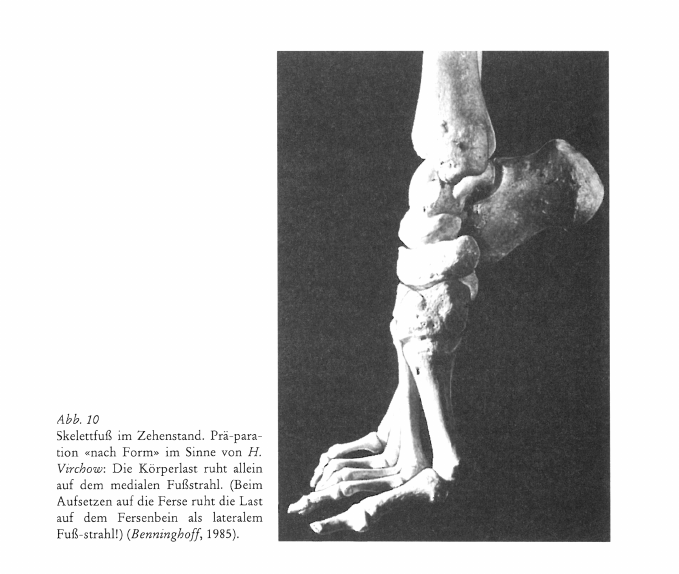

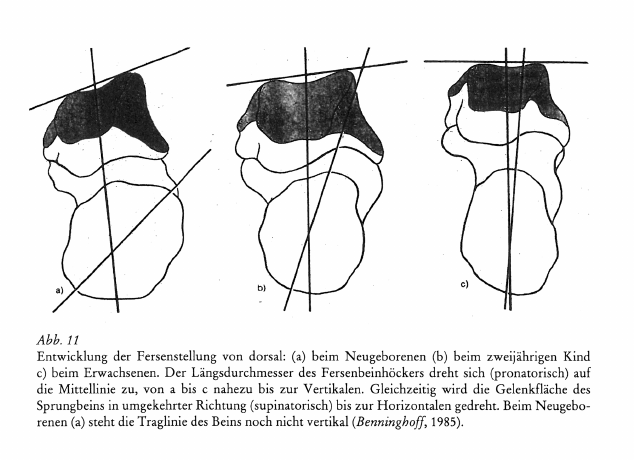

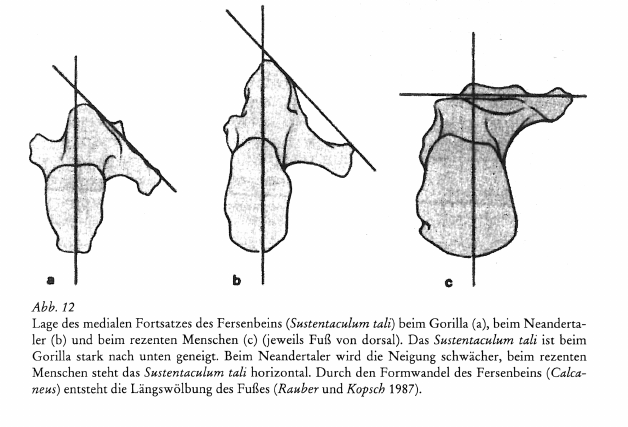

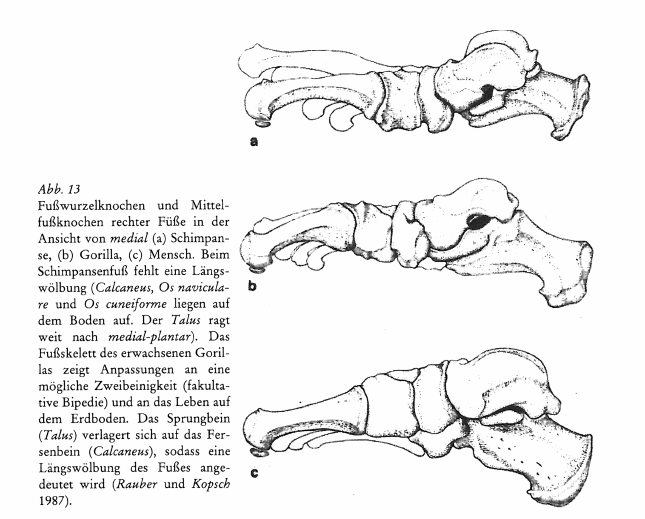

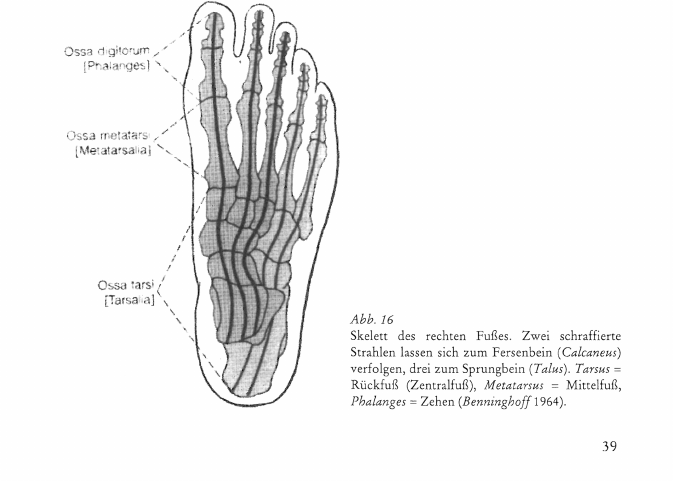

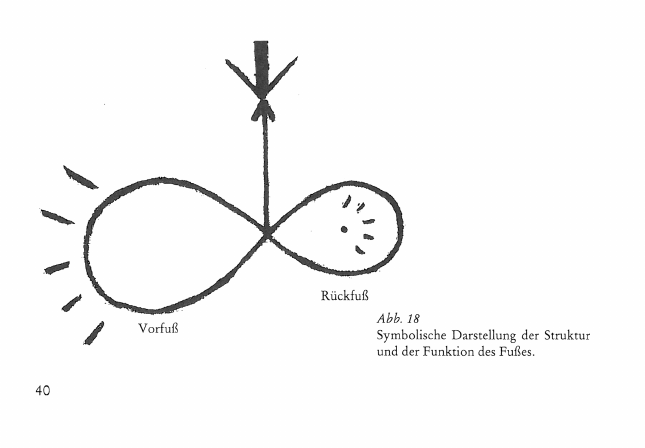

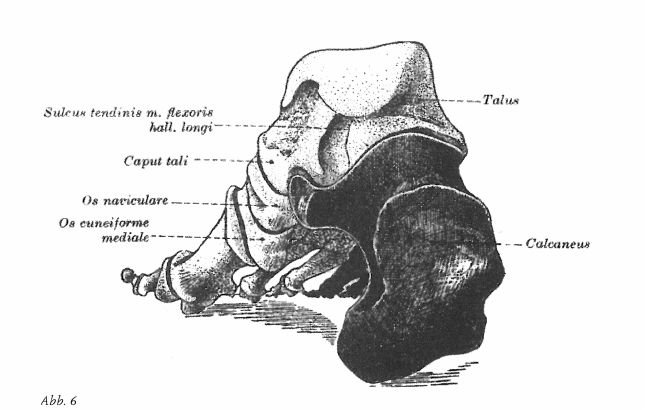

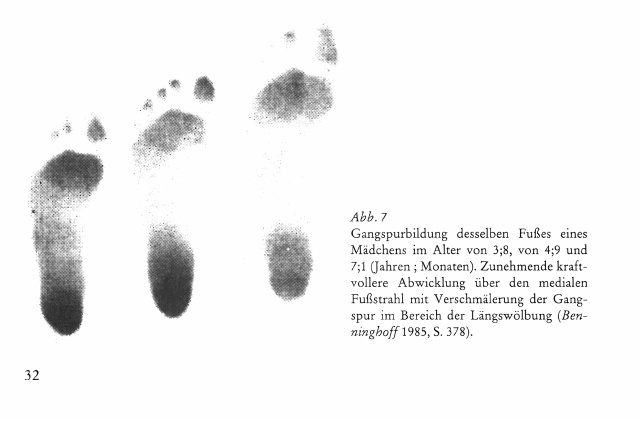

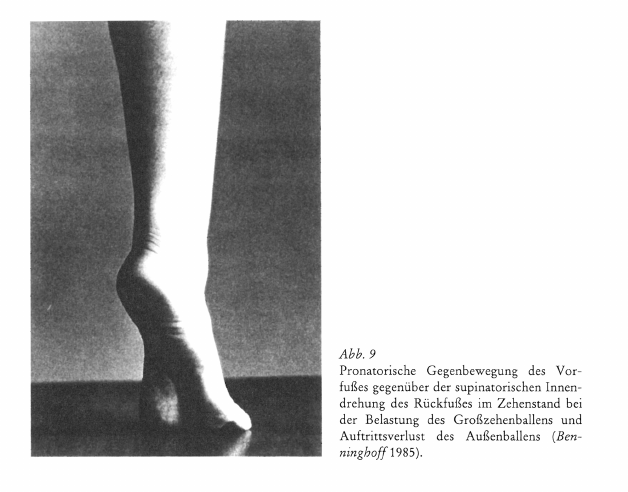

What is the significance of gravity in the formation of the human body? Here gravity is not defined physically, but instead a <sensory-moral> approach to experiencing it is first introduced. When the human form raises itself in the earth’s gravity field, a characteristic reshaping process of the foot takes place. In the sense of a torsion of the foot, the anterior foot undergoes a pronation and the posterior foot a supination, such that the latter gives rise to a building up of storeys. During these growth movements the arch of the foot develops and the foot takes on a lemniscatory form. This is connected with the effect during standing of the maximal load via the tibia from above corresponding with the point of inversion of the lemniscate. These special conditions in the case of man are compared with the apes closest to man. In man, the development of the anterior foot is polar to that of the posterior foot. The former conveys more a process of experiencing the world (<altruism>)‚ the latter an experiencing of the self (<egoism>). Inside the foot the same polarity rules as between the right and left halves of the body and between pronation and supination of the forearm. From the centre between these two polar formations (anterior and posterior foot) rises the erect body - in the bony formation of the legs - countering the gravitational load. In demonstrating the process of becoming erect, which is an imitative act, it emerges that the child’s personal efforts involved in the functional demand of standing up at the same time shapes the bones. Thus the I (ego) at work in the personal endeavours is also at work in shaping the body. The I has its effect always in the balance of two polarities (in the erect posture between right and left halves of the body, between anterior and posterior foot and between pronation [receiving] and supination [giving]).