Verstehen verstehen

Export Article Citation as

- Plain text

- BibTeX

- RIS format

- Download price : € 6.00

Abstract:

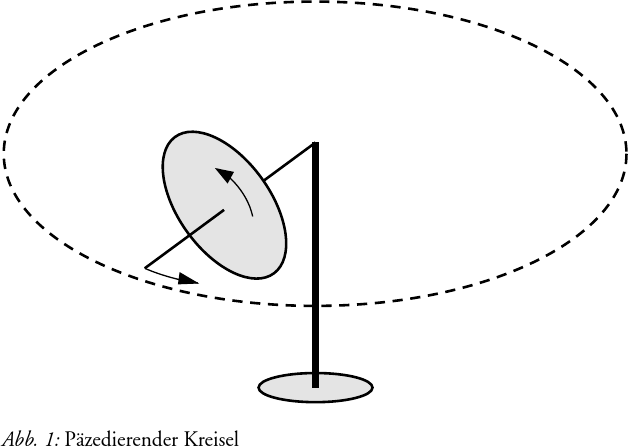

In vol. 73 of this journal Johannes Kühl (2000), with reference to Rudolf Steiner’s so-called Bologna lecture, described, how he experienced the ‘I’ when studying the behaviour of a gyroscope. He explicitly formulated the objective of his study: “not only to understand [the gyroscope] conceptually, but to understand in an experiencing manner (erlebend nachvollziehen)”. As I failed to achieve this objective, I took the opportunity to produce what is called a ‘phenomenographic analysis’ of this process of non-understanding. (Phenomenography is a recognised method in phenomenologic research of learning processes). As the method applied here of chaining non-understanding to understanding (Buck et al. 2002) may lead to a wider intersubjective understanding of both the gyroscope and the issue raised in Steiner’s Bologna lecture, it was considered worthwhile publishing the results in this journal.

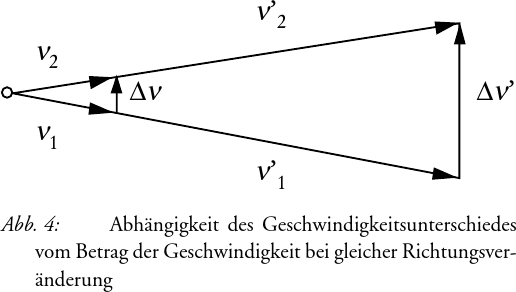

Since in phenomenography, understanding can only be investigated indirectly from texts, (written) texts by Steiner, Kühl, Feynman and the author were taken as a basis for describing the content and process of individual understanding of both the gyroscope and Steiner’s statement. The discrepancy in Kühl’s and Buck’s understanding turned out to lie in Kühl’s explanatory approach combined with his use of traditional scientific (physical) terminology and methods (which usually show a tendency towards eliminating individual experience) where Buck had expected a phenomenal descriptive approach. A second discrepancy turned out to lie in the phenomenon treated: whereas Kühl focused on the phenomenon ‘behaviour of the gyroscope’ (which is an abstract phenomenon), Buck had expected the ‘gyroscope as an integral phenomenon’ (which is closer to perception) to be discussed.

Although the means used by Kühl failed in the case of Buck’s understanding, both individuals agreed in their self-appraisal of the ‘location’ of subject and object during a genuine understanding process: It is the [mathematical] relationship between subject and object that makes up the understanding process, thus any separation between the ‘I’ and the [mathematical or other] content of a cognition disappears on introspection of any genuine understanding process.